It is not difficult for a mother, a writer, like me to imagine what it must be like to celebrate 19 Christmases without one of my children. Decorating the tree would be especially hard. A shining ornament would be left in a box, unwrapped, untouched by anyone’s hands except little Levi’s, a sacred reminder that his fingerprints were once there. A styrofoam ball covered in red and green glitter that Levi made in second grade would sit impatiently in its cardboard box, waiting, waiting but no one comes for it.

Or, maybe his ornaments are gone, heaved into a trash bin along with the floorboards and plasterboard from his room. Maybe the doorway through which Levi once strode, dripping wet with laughter and creek water, is gone. Sealed off. Moved aside. The ghosts of Christmas past. And, imagination is replaced with the blinding light of facts.

It was Wednesday, Oct. 22, 1997, when Levi Frady, 11, went missing while allegedly riding his red, 20-inch bicycle near his Burruss Mill Road home.

His body was found the following day by deer hunters in the Dawson Forest Wildlife area, approximately 19 miles — and one county away — from his home.

Frady had been shot three times, once in the upper body and twice in the head, according to authorities familiar with the case. Further, the three shots were not all fired at the same time or at the same location.

‘You were the best friend I ever had’

Levi and his cousins Arliss and Justin were as close as three beans in a chili pot. The trio spent the endless hours of boyhood baiting worms on rusted hooks, sloshing through the creek near Levi’s home and taking three hour hikes across wild, adventurous spaces unknown to anyone but them. These were boys whose blue jeans were happily dirty and riddled with small holes where tree branches had caught them and refused to let go. On the weekends, the boys built bicycle ramps and took turns “getting air” under their wheels.

Levi’s paternal grandfather, Lamar Frady, took Levi and the boys to the annual Forsyth County Fair where Levi’s favorite ride was the Typhoon. They were good at the carnival games and ended the evening with armloads of stuffed animals and small plastic treasures. Pizza filled their bellies full, and the only thing Levi enjoyed more than that was his grandmother’s pancakes.

He was one of 12 grandchildren.

Nine years after Levi’s murder, Justin still grieved. He took up a pen and poured his emotions into a poem that he sent as a letter to the editor of the Forsyth County News. It was published March 6, 2006.

“What were we, ten? When Nanny used to call us her little men? … We’d rush down the yard and climb up our tree. We’d sit there and stare as far as we could see. I remember the good times. There were never any bad. You were the best friend I ever had. I can’t help but to cry. …But even though you are gone, we know that one day we’ll each get our chance to meet you at the golden gates. And after they are opened, we can spend eternity as friends.”

Christmas was Levi’s favorite time of year. What child doesn’t love Christmas?

“He loved giving presents, and he always helped the little kids with theirs. He was such a good boy, and he had such a big heart,” said Janice Hamby, Levi’s maternal grandmother, according to a Dec. 21, 1997 Forsyth County News report.

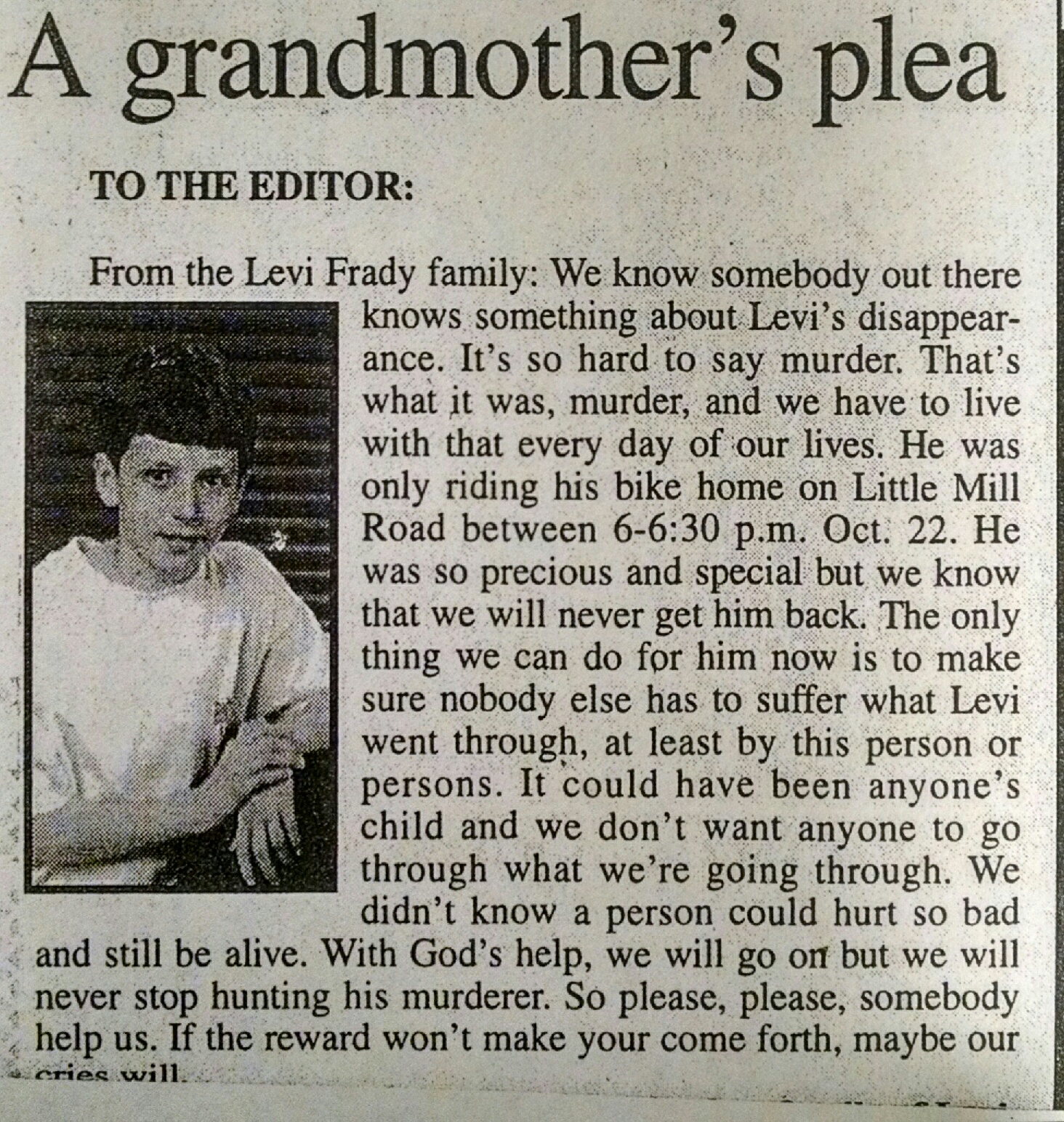

Hamby also wrote a letter to the editor of the Forsyth County News, seventeen days after her grandson was murdered, begging the community for help.

Two years of investigation, research and interviews

After church on a rainy, cold afternoon in the spring of 2013, I was sitting on the floor of the Dawson News & Advertiser office. It was a quiet time. A time to think and to plan. No phones. No customers. No police scanner beckoning me from its spot in the corner. The newspaper was established in 1887 and if you didn’t know any better, you’d swear the tile where I sat was equally old. My task was to organize the unorganizable — decades of yellowed, flaking newspapers. That was when I came across this headline: Child’s Body Found in Dawson Forest WMA. The date was Thursday, Oct. 30, 1997.

“The body of an 11-year-old Forsyth County boy was found in Dawson Forest Wildlife Management area (WMA) off Highway 9 in Dawson County last Thursday,” according to the article. “Dawson County Sheriff Billy Carlisle said three hunters found the body of Levi Dillion Frady in a remote section of the WMA about 2:30 Thursday afternoon.”

Levi Dillion Frady. It was the first time I knew his name. From his age, I knew he was the same age as my daughter.

“Levi was fatally shot,” said Carlisle. “This case is a homicide.”

Why would anyone shoot a little boy? skidded through my brain.

Eager to find the answer, I blew dust off another stack of papers, and spied this Nov. 13, 1997 headline: Law Enforcement Optimistic About Solving Frady Case. And this: Search Continues in Levi Frady Homicide. By Thanksgiving, an FBI agent was called to assist. At Christmas time, the Forsyth Shriners Club added Levi Frady to their reward fund, a fund which over time grew into the largest in Forsyth County history, topping $125,000.

A billboard with Levi’s picture was put up on Highway 9 in Cumming. A one-year anniversary was recognized, a letter that may lead to the boy’s killer surfaced, a suspect was interviewed. But, my question remained unanswered.

Other murders were solved, other victims whose bodies were also found in Dawson Forest: Cameron Green in July 2003, Meredith Emerson in January 2008.

On weekends and in my spare time, I worked on Levi Frady’s case. What mother, what curious news reporter wouldn’t? I had to know. Who murdered Levi?

Who is telling the truth?

It was a warm fall afternoon in September 2015 when I invited a retired Dawson County law enforcement officer to meet me at McDonald’s in Dahlonega. It was cheap and I was hungry. He wasn’t. So he sat with his thick legs folded under the plastic table and watched me eat. I noticed scribbled notes on his yellow pad. I noticed a flattened-out Happy Meal bag on the table. His blue eyes moved casually from item to item and back to me with an easy confidence, the motions of a man who knew what he was doing, what he was saying.

I noticed a man sitting alone in a booth across from our table. He feigned aloofness. Dark auburn hair. Straight. Mustache. A pock-marked, ruddy complexion. Late 50s. My eyes caught his and he quickly turned to his uneaten burger, but his ears were finely tuned on my table. An interloper.

My lunch guest got right to the point and said he called Billy Carlisle before meeting me. Carlisle is the sheriff of Dawson County where Levi’s body was found. He retires Dec. 31, 2016 seven days from today, after serving four terms and 20 years. He was in his first term when Levi was murdered.

“Billy and I are friends,” he told me as if what he said next was somehow more dignified, more pristine, truer.

“I’m glad we’re meeting here today,” he added. “This was Levi’s last meal.” He held up the happy meal bag with a somewhat dramatic flair and talked to me about french fries as I chomped down on mine.

“Potatoes digest fast,” he said. “There were still bite marks in the french fries in Levi’s stomach.”

The conclusion I immediately drew was obvious — Levi was dead before his happy meal had tme to digest.

“How do you know?” I asked.

“I was there when they did the autopsy,” he said.

It wasn’t that his words surprised me; it wasn’t the way he dropped them like heavy snow falling off a roof; it was the way he waited for my reaction. A member of Levi’s family had already told me about a hamburger happy meal. To me, this was simply confirmation.

The question now is where was Levi when he ate the last happy meal of his life? How much time elapsed between the happy meal and the first gun shot?

GBI took seven years to complete its timeline of events leading up to Levi’s murder. Between 5:30 – 5:45 p.m. Levi’s mother and sister arrive home bringing carry-out food from McDonald’s Restaurant (hamburgers and french fries), according to the timeline.

It is not far-fetched to think GBI analysts can, and have, determined how much time passed between the two events.

My mind rolled through a dozen questions I wanted to ask, but instead I let the retired officer talk. I could tell that’s what he wanted. He checked his notes.

“Who do you think killed him?” he asked.

So I told him. An unfamiliar kind of nervousness seemed to creep across the table and settle in his lap.

“Who do you think killed him?” I asked.

He too quickly blurted a name. A name I cannot repeat now because of what happened a few days later.

I pulled open the heavy glass door leading into the Dawson County Sheriff’s office as I had done a hundred times before. Amanda was cordial behind her glass wall, but not friendly as she had been before I launched LeviFrady.com. To me, the lobby of the sheriff’s office was like a hospital. Concrete walls painted white, metal booths with attached metal seats, a sterile fingerprinting room, the same room where I was fingerprinted for a concealed weapons permit.

Carlisle’s office is on the second floor, always has been. He met me as I opened a set of creaking metal doors leading into the dark blue belly of Dawson County law enforcement.

“I saw you coming up in the elevator,” he said.

I followed him down a narrow corridor into his neatly organized office. He kept a picture of his wife cradling their grandchild on his desk. Behind him were multiple monitors of the jail, parking lots, elevator, sally port.

Accustomed as he was to my recorder being turned on when we talked, I turned it off, hoping for a relaxed atmosphere. I sat down in the same fake leather chair where I always sat. The same chair where I asked him for quotes about a murder/suicide. Where he told me he’s not fighting commissioners anymore over his budget. Where he announced to me his retirement.

And where he told me Levi Frady’s case still haunted him.

My years of getting to know Billy Carlisle were woven into a cold tapestry of crime and criminals, of politics and policy, but during that time, I found him to be honest and hard-woking. He told me what he could tell me, nothing more. I had news stories to write and he was one of my sources.

Billy’s friend had divulged to me who murdered Levi, but I needed the information triple checked. It couldn’t be this easy. Or, could it? Could the vast weight of secrecy on an aging mind cause it to burst forth with unexpected revelation?

I told Billy who his friend believed murdered Levi.

“That’s ridiculous!” he said as his neck and head reddened to the shade of a sliced tomato. He brushed away my words like lint.

Without being asked, the retired officer had also told me no drugs were involved. No sexual molestation of the boy. He revealed he had a copy of the GBI file that he’d share with me.

“It’s buried somewhere up in my barn,” he said. “I’ll have to see if I can find it.” I never heard from him again.

What I know now that I didn’t know then

A confidential letter from Forsyth County Sheriff, Denny Hendrix, to GBI Director Vernon Keenan reveal that crime scene photos, polygraphs, interviews, and a search warrant were withheld from him. Levi was allegedly abducted in Forsyth County. Yet when Hendrix arrived in Dawson Forest, where Levi’s body was found, he was told by a district attorney to leave.

In early April 2000, after receiving a petition with 2,000 signatures from the Frady family and concerned residents from Forsyth County, Hendrix assigned two detectives to form a joint task force to take a fresh look at the case.

During a videotaped 2013 interview at the Forsyth County Sheriff’s Office, Tommy Albert Samples said he was hit or stabbed by Marshall Tallant with the gun that was used on Levi Frady. No search warrant was issued for Tallant’s home.

Marshall Tallant’s cousin, Jackie Tallant, served little time in jail despite repeated drug and weapons charges. Both were friends of Levi’s mother, Marilyn Parkman, and her boyfriend, Tim Tatum.

GBI’s timeline shows family members took Levi’s bicycle and did not notify authorities he was missing until after they put it back the following day. Two law enforcement officials familiar with the case said the bicycle had been wiped clean of fingerprints, even Levi’s.

There was no accounting system in place to track drugs or money seized by a joint Forsyth/Pickens/Jasper drug task force headed by Forsyth Capt. David Bennett. Nearly $28,000 in drug money went missing.

On September 19, 1997, about one month before Levi was murdered, Forsyth Sgt. Lynn Payne — a member of the Forsyth Drug Task Force under David Bennett — was suspended without pay after two juveniles were arrested with drugs allegedly found on Payne’s property. Two days later, Payne resigned. No charges were brought against him.

Levi called 911 one or more times in the days leading up to his murder.

No one saw him be abducted.

There was no blood in or around the area where Levi was found, according to Rev. Larry Kelly who first found the boy. Kelly’s statements are diametrically opposed to a GBI agent’s who told the public there was a pool of blood and signs of a struggle.

(Editor’s note: Supporting documents and details of items summarized here can be found throughout LeviFrady.com).

“He was only eleven”

Four days before Christmas 1997, the first Christmas without Levi at the Frady house, his maternal grandmother, Janice Hamby, poured her grief into a poem published by the Forsyth County News.

He was only eleven / So full of life and fun / Why do children have to pay / For things they’ve never done

He was only eleven / And had his whole future ahead / Birthday parties and school dances / But now he is dead

He was only eleven / He didn’t seem to have a care / But now when I go to get him / I realize he’s not there

He was only eleven / Are children easy prey? / They are so trusting / They believe what you say

He was only eleven / What did he have to give? / Not anything you wanted / Why didn’t you let him live?

He was only eleven / and everyone has to die / We’re happy he’s in Heaven / But missing him makes us cry

Nineteen Christmases later, Levi Dillon Frady’s murder, remains unsolved.

Link to first LeviFrady.com news post

POST A COMMENT

SHARE A LINK WITH YOUR FRIENDS ON FACEBOOK

Credit for cover photo of Janice Hamby and Marilyn Parkman (Levi’s mother): Tom Brooks, Forsyth County News, Dec. 21, 1997

©LeviFrady.com 2016-2023. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Contact: Kimberly@levifrady.com

Was the deputy interview Steve Hawk?

LikeLike

So a little boy is abducted and murdered- shot, possibly in the back, three times! His body is dumped in Dawson Forest. Neither FC or DC or hell even the GBI wanted the murder solved. Seems that a good number of townsfolk don’t want it solved either-but others are saying

” they know who committed/had him murdered and why he was killed”.

Over thirty years later it’s still confusing, suspicious, and very sad! and yet nothing has changed!-There is no statute of limitations on murder.

RIP Levi

LikeLike

Just a thought…. how did Levi have undigested mcdonalds French fries in his belly if he was already gone when his mother and sister arrived home with burgers and fries from McDonald’s? Did the abducter feed him before he was killed?? It just doesn’t add up according to the timeline.

LikeLike

You sure one of the own Frady’s didn’t do it? That family is crazy/wild as hell. Why didn’t they keep up with their young boy? I feel like all those children are so neglected.

LikeLike

That’s a lot to accuse someone of. He was in the care of his mother, not the Fradys, when he went missing.

LikeLike

Are you stupid? Who are you to sit here and think that ANY of the Frady kids are neglected? Not one of us has ever needed for anything… ever. Always been fed, housed, and clothed. Levi was not under the care of the Frady’s when he went missing. Had he been the odds are that he would not had been left to ride his bike home at dark. I’d sure like to know which of the Frady’s you think would have hurt Levi and why… And please let’s hear personal experiences… not what your sisters boyfriends cousin heard from his cellmate while he was in jail.

LikeLike

Clarification on the above post- He wasn’t hurt, he was murdered.

LikeLike

Will there be more updates? I’m interested in whether Tim Tatum was investigated, and who in the police force had something to lose by the case being solved. Three dysfunctional departments, Forsyth, Dawson, and the GBI, broke their necks trying not to solve this case. There’s a lot more to this story and hope to see more in the future.

LikeLike

What’s wrong you run out of lies to write about?

LikeLike

Also what happened a few days later that prevents you from giving the name that Carlisle’s friend gave you at McDonald’s?

LikeLike

She met with Sgt. Billy Carlisle and he said it was rediculous. Thats what happened.

The source led with Levi’s last meal knowing that Marylin had brought home the same food. I’m interested in who she thought it was also. She hinted at it with her immediate response to his McDonald’s lead-in. I think she said Marylin or Tim Tatum, to which he didn’t agree, or else he would have said “right”, skipping naming one himself.

Seems weird that he ate the same meal as his family, but never made it to his house. I wonder if GBI scrounged through Marylin’s trash to see if his meal was touched. God knows FC and DC didn’t, not smart enough. The source brought the bag for a reason. She plainly said he didn’t eat, means he didn’t order anything. Why bring the visual? It had a purpose, she even stated she believed he was being purposeful.

On a side note, if the bike had no finger prints, and his family brought the bike back, seems to me they had to be the one to wipe it or their finger prints would have been on it. It also gives them a semi-legitimate reason if someone saw them dumping the bike. My question is why didn’t they go knock on the door of the house where they had originally found the bike? “Levi was here last, let’s get the bike. Right?” Who gives a care if the bike gets home, what about Levi. He might even need it to ride home on if he shows up. He knew where he left it. Something isn’t adding up there. Then another family member saw Tim Tatum by Dawson Forest that morning. Fishy!

LikeLike

I would also like to know more about the 911 calls…

LikeLike

He was afraid of something. Why else would a child call 911? They have to be severely worried about something. Most kids know by 11 that pranking 911 is a good way to get in trouble. Levi didn’t want to get in trouble much from what I hear.

LikeLike

What were the 911 calls about?

LikeLike